For Yourself, and For the Child:

Gentle, lntentional Movement for Everyday Neural Plasticity & Change

Excerpted from

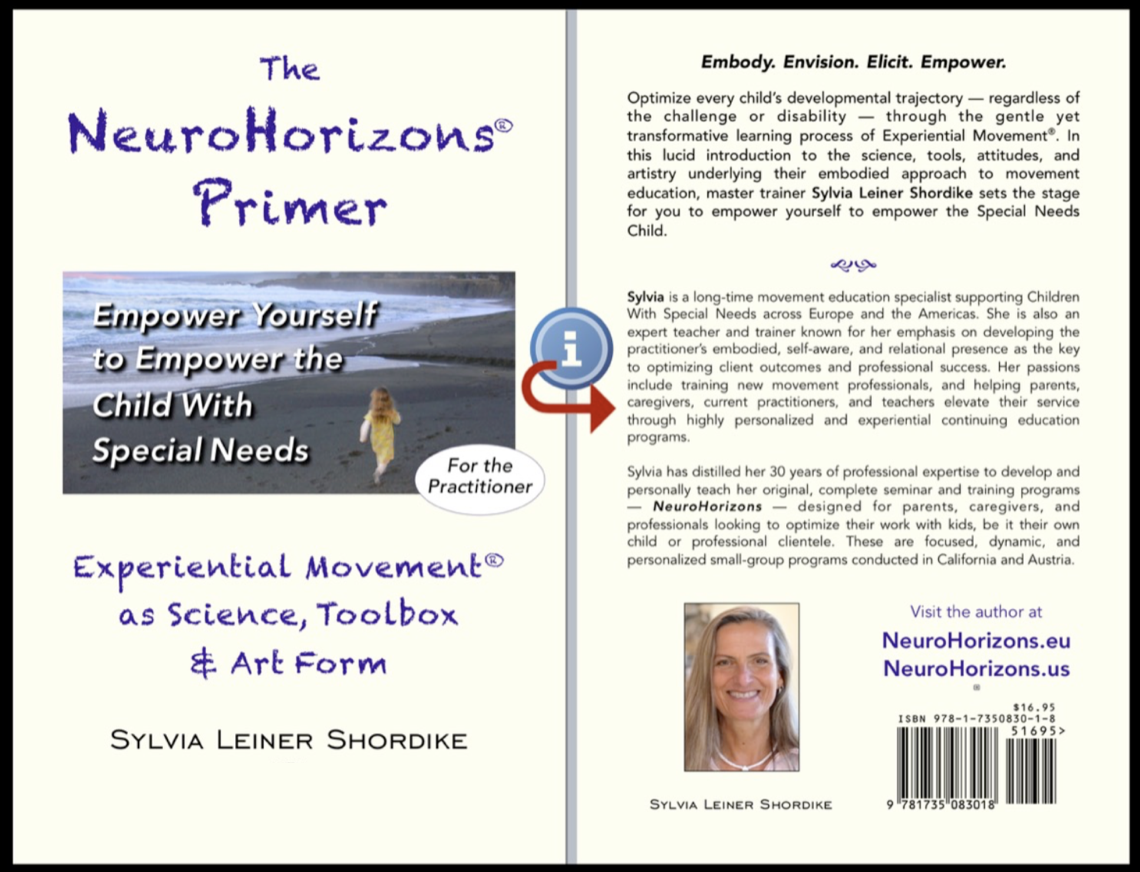

The NeuroHorizons Primer

If we are alive, we are constantly in motion, even those of us with challenging physical limitations or disabilities. The skeleton moves. Muscles and tendons move. Tissues move. Organs and glands move. Blood moves. Hormones move. Neurotransmitters move. Within and around every cell of our body countless components of life are in continuous motion. And, every part of the body is connected through movement to every other part.

Most importantly for purposes of this Primer, the human brain learns and orients through movement. During waking hours the nervous system is largely occupied with the countless and unceasing movements noted above. That is, movement organizes our perceptions, interpretations, feelings, thoughts, intentions, and actions. Our very consciousness ― and that includes new learning ― relies on movement.

It follows that attentive and intentional movement is a great way to communicate with the nervous system, and to re-organize and enhance our life. Put another way, the awareness we bring to the character and quality of our movements ― whether we be adult or child ― will largely determine the character and quality of our experience of life. This foundational concept guides our work with Children With Special Needs. As practitioners, personal awareness of our own quality of movement underpins our ability to offer transformative learning opportunities to our young clients, who do not yet have such self-awareness.

Paradoxically, we often know good movement when we see it in others, but generally are unaware of it in ourselves. We love to watch elite athletes and how they move, or a fluid dancer, or musician, or martial artist. Conversely, bring to mind an occasion when you glimpsed a stranger in the distance, and immediately identified that person as “frail”, or “elderly”, or “disabled”. You most likely came to this conclusion instinctively, based on the person’s posture, gait, balance, and use of head and limbs ― that is to say, their quality of movement.

Yet, how aware are we at any given moment of the intention, quality, and outcome of our own movements? Ask yourself: “Right now am I aware of my breathing, posture, pulse, or muscle tone? How conscious am I of the motion I just made? As I sit, stand, or walk, am I at ease and balanced, or tense and straining? Do I feel integrated and whole and “present” in my own skin, or scattered or stressed? Am I living so much in my head, intellect, anxiety, or daydreams that I cannot readily answer these questions? Have I wondered lately whether my life is moving too fast? Might I benefit from slowing down and becoming more attuned to my inner landscape? What keeps me from doing so?”

Genuine embodiment can be challenging even for “healthy” adults (we movement professionals included). Now consider a child with developmental challenges. Many disorders, diseases, and delays experienced by children interrupt the normal “conversation” that takes place between a child's nervous system and the “outside” world. Lack of full and free movement is a common element of these challenges. As just a few examples:

A child who suffered a perinatal stroke or has cerebral palsy may have severely spastic limbs, preventing fluid, integrated, or fully bilateral movement; or, a genetic disorder may result in a constricting skeletal or brain malformation; or, a traumatic birth experience may lead to a rigid or listless baby who cannot readily tap into the usual developmental movement experiences; or, a kid with ADHD acting on impulse may not yet have the resources to attend to his inner landscape and develop a sense of self-agency and control; or, a child on the autism spectrum might be easily overwhelmed by any activity outside a very narrow internal comfort zone.

Any such limitations present a dilemma for the child: Normal development is a progression of learning through movement and sensation, and the child may be missing key experiences that the nervous system needs in order to take a next developmental step.

This is why we often find a Child With Special Needs at an impasse: He may be missing the prior experiences required for optimal learning. For example, if the infant does not make use of the relationships among head, spine, and pelvis, he cannot learn to transition between positions, such as by flexing and rolling. It will be difficult to functionally use the arms and hands to push. There will not be a pliable spine and mobile pelvis. Hence, the self-generated skills of sitting, standing, and walking will not be possible to master.

In other words, if certain interim movement experiences go missing owing to developmental deficits, the child cannot easily sequence his way to the next step. There is no “fast forward” button we can press to simply skip over those experiential gaps to arrive at the desired “developmental milestone”.

Fortunately, it is nearly always possible to use gentle movement and sensory experiences to begin a new conversation with the nervous system of a child. Regardless of the diagnosis or developmental challenge, most young brains are available and ready for such kinesthetic learning and a transformational journey. As practitioners, our starting point necessarily is the developmental impasse at which we find the child. That is, we meet each child where she is, not where we or a parent might think she is “supposed to be”.

Through the Experiential Movement Lessons we discuss a little later, the child's brain and nervous system eventually receive and assemble the information, experiences, and conditions required for new abilities and mastery. With the practitioner’s insight, skill, and patience, these Lessons can mitigate or even remedy many of the developmental gaps and deficits caused by various conditions and traumas. The child can then natively do, and be, in ways not possible before.

Key to our understanding is that the body is a collection of neural networks. Each such network is a grouping of nerve cells that “fire and wire together” and are responsible for some aspect of how we experience, perceive, interpret, react to, and move in our environment. Repetition strengthens existing neural networks: The connections we use the most become stronger and endure ― whether for good or ill.

We humans universally define and view ourselves through these habituated, and largely unconscious, neural patterns. Some such patterns are useful, such as never forgetting how to write our name, ride a bicycle, tie our shoe, or brew our morning coffee. But neural networks also account for why even our acknowledged “bad habits” can be so hard to break ― and we all have more than a few of these. The engrained patterns have become our “default” mode, our “autopilot”, the path of neural least resistance.

Conversely, think of a time you felt satisfaction, even excitement, learning or experiencing something (or someone) new. This is the pleasure of new neural networks forming ― the process of neural plasticity. New networks can be formed even in our adult and aging brains, and eventually displace the primacy of older patterns and habits that no longer serve. Yet, this does not always happen on its own; we often must intend to make it so, or at least welcome rather than resist new information and experiences when they knock on the doors of our awareness. As practitioners, both our personal and professional work is about opening those doors ― for ourselves and for our clients.

We are all born with this capacity for neural plasticity, through which our nerve cells change the way they are shaped and relate to one another in existing or newly-created neural networks. Both structurally and functionally, new neural communications and patterns arise in response to environmental factors, social interactions, and new information and stimuli (such as the Lessons we explore for ourselves, and offer our clients). It is such “newness” in our life, not the familiar “been there, done that”, that best activates our learning process.

And, as we have noted, movement is an everyday yet potent way to elicit these changes. This is why we engage our clients in novel and varied movement, while emphasizing the “experiential” of Experiential Movement. As noted, children are particularly receptive and adaptive when it comes to creating new neural networks. Hence the effectiveness of our intentional movement work, especially when offered in a manner that helps the child to feel safe, affirmed, and loved.

This learning process relies, first and foremost, on our confident embodiment of these movement principles for ourselves. That is, we slow ourselves down and get friendly with our own attentive and unhurried process of forming new neural networks. We are then present enough to envision and move with a child in ways that evoke and empower his own experiential learning. Together, practitioner and child create a “safe container” and attend to novel and varied movements, unveil new neural horizons, and embark on new developmental trajectories. We will talk much more about this joint adventure throughout the Primer.

We will say it in different ways over the following pages: The child is receptive to new learning, no matter the challenge. As embodied and relational movement practitioners, both our personal and professional work is about opening these doors ― first for ourselves and then for our clients. We identify creative and meaningful ways to gently dance with the child’s native resources. This is what allows both client and practitioner to move beyond the existing map toward new neural networks.

This profound appreciation ― that a child’s current neural map is not the territory ― is key to how we elicit and nurture the child’s native learning process, empowering her to journey toward each new developmental horizon.